Bigger Isn’t Always Better: What the Proposed Agribusiness Mega Mergers Could Mean for Canada

By Jennifer Clapp, Chelsie Hunt, and Carly Hayes - University of Waterloo

Update September 14 : Bayer signs deal to acquire Monsanto for $US 66 billion.

German drug and farm chemical maker Bayer AG says it has agreed to acquire seed and weed-killer company Monsanto in an all-cash deal valued at $66 billion. Read More on CBC website.

|

This topic will be one of the many issues debated during Resetting the Table, FSC’s 9th Assembly (Toronto - October 13-16, 2016). |

The agricultural input industry is already highly concentrated with the “Big Six” (Syngenta, Dow, DuPont, Monsanto, Bayer, and BASF) controlling 75% of agricultural input sales globally. But the players are going to be even fewer if these corporate giants are allowed to pursue a series of mergers and acquisitions that will transform the sector.

It began last year, when Monsanto began offering bids to purchase Syngenta, a deal that ultimately fell through. Not to be left out of the game, Dow and Dupont announced in December they were tying the knot with a $130 billion merger in a deal that will ultimately create three new firms, one of which will specialize in agricultural chemicals and seeds. Then, in February, ChemChina announced its plans to acquire the Switzerland-based company Syngenta for $43 billion. Lastly, in May, Bayer offered $62 billion to acquire Monsanto, the notorious producer of Round-up herbicide and Round-up Ready seeds. It’s not even clear that the merger frenzy is over, as BASF has been left the odd firm out, and it may yet strike a deal to keep up.

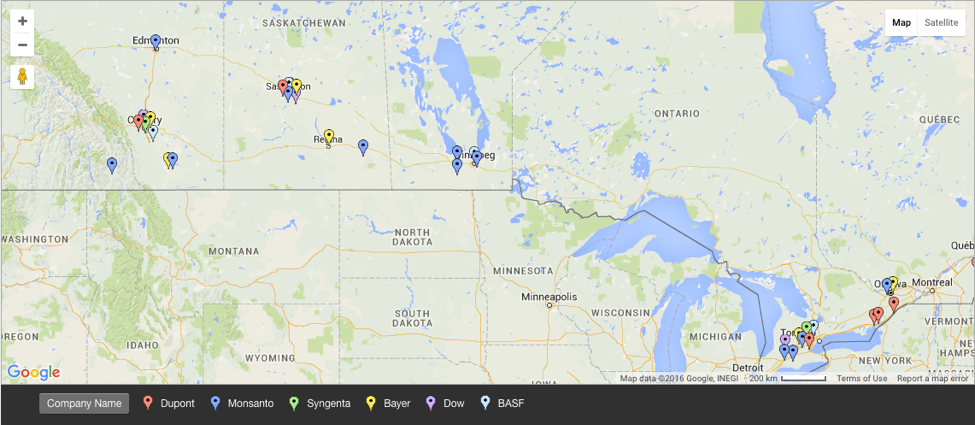

What does this transnational corporate shake-up mean for farming and food security in Canada? According to ETC Group, in 2013 the top six firms held 75% of the global agrochemical market and 63% of the commercial seed market. The ETC Group estimates that if the proposed mergers proceed, just three firms will control over 65% of the agrochemical market, and over 60% of the seed market. Country specific data on market share for these firms is difficult to find, but if these global figures are any guide, the mergers will have a profound impact in Canada. With over 35 Canadian operation locations staffing thousands of employees, the “Big Six” have a large presence in Canada (see figure). Each actively sells seeds and/or agrochemicals in the Canadian market earning millions of dollars each year. Last year, for example, Monsanto’s sales in Canada topped $600 million.

The Big Six: Operation Locations in Canada

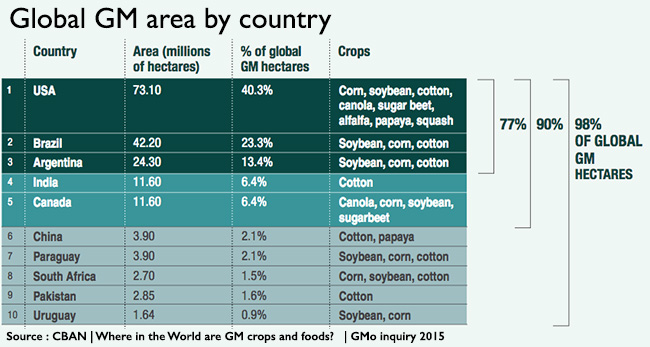

The Big Six firms specialize in crop protection chemicals and seeds, and increasingly are focusing on proprietary seed and chemical combos that work as a ‘package’– typically genetically modified seeds that are bred to resist specific brand-name chemicals. In Canada, a large proportion of canola, corn, and soybean crops are genetically modified, and the proposed mergers and acquisitions would reduce farmers’ choices of suppliers for these seeds and their associated crop protection chemicals.

Canola is Canada’s second most valuable crop, and this year farmers have planted over 19 million acres of it. According to the Canola Council of Canada, in 2010, 47% of canola seeds contained genetically modified traits developed by Monsanto (Roundup Ready) and 46% contained genetically modified traits developed by Bayer (Liberty Link). If current figures are similar, and if Bayer’s bid to acquire Monsanto is accepted, over 90% of Canada’s canola crop will be tied to traits controlled by just one firm.

The number of suppliers for corn and soybean seeds is also likely to shrink in Canada. According to the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network (CBAN), over 80% of Canada’s corn crop and over 60% of its soybean crop are grown from genetically modified seed. In the US market, the top four firms – Monsanto, Dupont, Dow and Syngenta (all firms involved in proposed mergers) – together currently hold 80% of the corn seed market, and 76% of the soybean seed market. The Canadian market for corn and soybean seeds is likely to be similar to that in the US because a high percentage of these crops in both countries are produced from genetically modified seeds, meaning that the mergers will concentrate the seed supply for these crops into fewer corporate hands.

If the mergers proceed, the effects will go beyond reducing the number of seed suppliers. Bayer claims that its proposed acquisition of Monsanto stands to create $1.3 billion in “synergies” (that is, cost savings). Some analysts worry that these savings will come from cost cutting in the research and development divisions of the firms once they are merged, which could stifle innovation. The ETC Group points out that the number of new active ingredients in agricultural research and development has declined by 60 percent between 2000 and 2012, a period of earlier consolidation in the industry. Budget cuts are also likely to lead to job losses, which is a particular concern in Canada, as all six companies currently have Canadian R&D operations.

As mega-companies corner a greater share of the market, the number of seed varieties in the hands of farmers could shrink due to cost cutting tactics and reduced incentives to innovate. The mergers thus have the potential to narrow the genetic base of Canadian agriculture, creating greater vulnerabilities to crop failure and reduction of the overall biodiversity base of the country.

If the Big Six are reduced to just three or four major firms, their pricing power will be enhanced, and farmers could face higher prices for seeds and chemical inputs. Any increased cost of production is likely to be shared with consumers, meaning that the food on Canadian grocery store shelves will become increasingly expensive, exacerbating food insecurity for vulnerable populations in the country.

Consolidation of these already large companies into mega-corporations would also increase their lobbying power in Ottawa. Increased influence in Canadian agricultural policy by these companies will likely see a crowding out of voices advocating for alternative food systems, such as organic and small-scale farming operations, as the “Big Six” companies generally prefer an industrial agriculture model.

While it may seem like the mergers and acquisitions of agricultural input giants is too far up the supply chain to impact our daily interactions with food, the implications can start a domino effect that will flow right down to your local grocery store and affect the price of food for all Canadians.

- Jennifer Clapp is a Canada Research Chair in Global Food Security and Sustainability in the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo

- Chelsie Hunt is a Master of Environment and Business student in the School of Environment, Enterprise and Development at the University of Waterloo

- Carly Hayes is a MA student in the Global Governance Program at the Balsillie School of International Affairs, University of Waterloo

Thanks are due to Rachel McQuail for editorial assistance

Join Resetting the Table to discuss this issue!

Share your views:

- Log in to post comments