Hunger still thriving in Canada, particularly the North

“This article was published on September 25, 2015 for Food Secure Canada's Eat Think Vote campaign"

Members of the Northern and Remote Food Network of Food Secure Canada developed this op-ed and the proposal within it, which was published in the Winnipeg Free Press. The authors are academics and experts from all three northern Territories and various universities across the country. The full list of authors can be found at the end of the article.

For the last four years, the Remote Food Network’s work has drawn public attention to the food security crisis in Canada’s North.

“Finish your dinner! Somewhere in the world a hungry child would love to have yours!” This age-old reminder of inequality has lost none of its poignancy. How likely are you to think about food insecurity tonight at the dinner table? How likely are you to remember that ‘somewhere in the world’ is right here in your own country?

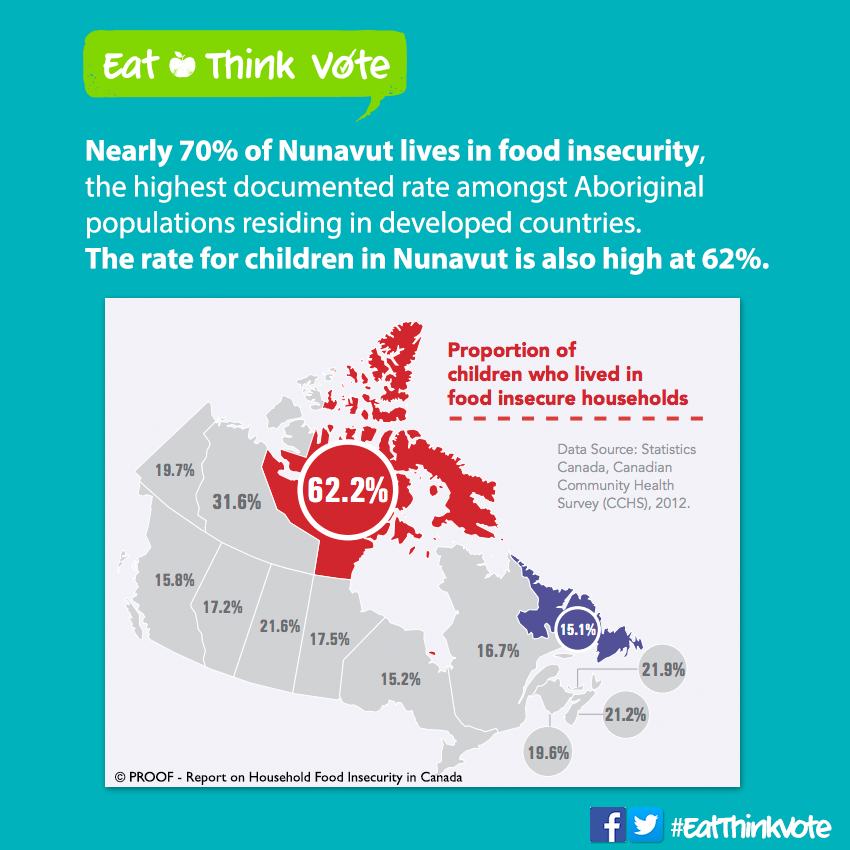

Food insecurity – the lack of nutritious, culturally appropriate food – is a persistent reality across Canada. In 2011, one in eight households experienced some level of food insecurity. That means 1.1 million children were affected. For Indigenous peoples living in the provincial and Far North, the situation is even more extreme: for instance, 70% of adults and 62% of children in Nunavut, as well as 60% of on-reserve households in northern Manitoba are food insecure. According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, these rates of food insecurity are six times the national average and “represent the highest documented food insecurity rate for any Aboriginal population in a developed country.”

Food insecurity is a serious threat to Indigenous people’s health in Canada, and particularly in the north. Mothers in northern communities must resort to feeding their children powdered ‘juice’ or condensed milk rather than formula and ‘tummy fillers’ like pasta and rice just to get by. When children don’t get enough good-quality, nutritious food, their ability to learn, remember and manage emotions is affected. Poor diet can lead to anemia, cavities, lowered immunity, obesity, and higher rates of chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and even rickets. (A recent study found that northern Indigenous children were six to twelve times more likely than other children to develop rickets.)

The causes of northern food insecurity are complex. It results from a combination of poverty, geography (many communities are accessible only by plane or briefly by winter roads and summer sea lift), colonialism and lack of access to traditional land-based food, combined with ill-conceived government programs and corporate practices. The legacy of the residential school system continues to play a big role, having broken the cycle of learning about how to hunt and gather food.

The current government approach to address food insecurity in northern Canada is a food subsidy program called Nutrition North Canada (NNC). NNC is paid directly to retailers and the store is expected to pass on those savings to the consumer at the point of sale. However, with zero oversight, there are serious doubts that consumers actually benefit from NNC according to the 2014 Auditor General’s report. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that there is almost no retail competition. The North West Company (NWC) receives almost 60% of the total Nutrition North Subsidy and also enjoys a virtual monopoly on the sale of food in the Canadian north. It’s no wonder that the cost of food in northern communities remains prohibitively high.

In 2011, the average cost of feeding a family of four for one week (according to the Revised Northern Food Basket - a standardized government measure) was $546 – a record high for any fly-in community in northern Canada. To make matters worse, NNC does not subsidize items necessary to pursue hunting and fishing activities such as fishing nets, boat motor parts, ammunition, and gas, nor does it support the purchase of diapers, toilet paper, hygiene products or medical devices. Some of the most highly subsidized foods are food that are not traditionally eaten by Indigenous peoples, imposing food choices on northerners that are not their own.

In 2014, the Auditor General of Canada released a report that criticized the effectiveness of NNC and called upon the federal government to address food insecurity in northern Canada. The report identified many areas of concern, including the fact that many northern communities are ineligible for the NNC subsidy. In northern Ontario, only 8 of 32 fly-in communities are eligible for the full subsidy, leaving many on their own when it comes to a hefty grocery bill.

In response to the Auditor General’s report, the Harper government promised to address the program’s deficits. However, when the MP for NWT proposed a motion in March 2015 that called for reforms to NNC that included the “addition of 46 remote communities currently ineligible for the program”, it was defeated in the House of Commons!

It is high time for the federal government to start listening to Northerners and Indigenous peoples in Canada who know best what they need to achieve food security. Providing sustainable funding for Community Food Coordinators in all northern communities is a first step toward inclusive and community-based solutions. There also needs to be a complete overhaul of NNC that includes financial support for hunting and gathering and own-food production, as well as federal regulation of the prices for food and other necessary goods and services. A basic income floor adjusted to reflect northern costs would go a long way to alleviating poverty more broadly.

These are essential ways forward to support Northern and Indigenous peoples in achieving sustainable food security by empowering and cooperating with them. It’s the first step towards a Canada where no child has to sit at the table hungry. Let’s start on that path today.

The authors:

Leesee Papatsie, Feeding My Family, Nunavut

Norma Kassi, Arctic Institute of Community Based Research, Yukon

Jackie Milne, Northern Farm Training Institute, North West Territories

Amanda Sheedy, Food Secure Canada

Kristin Burnett, PhD, Lakehead University

Sonia Wesche, PhD, University of Ottawa

Kelly Skinner, PhD, University of Waterloo

Myriam Fillion, PhD, University of Ottawa

Joseph Leblanc, PhD, Social Planning Council of Sudbury

- Log in to post comments